Stimulus, unemployment checks assist little one help debt assortment hit new excessive in California

Gabriel Lopez stands for a portrait while working at Homeboy Industries in Boyle Heights on April 19, 2021. Photo by Shae Hammond for CalMatters

SACRAMENTO, California. – If Billy McCasland had received his $ 1,200 stimulus check, he would have dragged his family out of the Modesto house, the pediatrician says he was responsible for the lead poisoning of his 7-year-old.

LA single father Gabriel Lopez said he was hoping to take his youngest to the Selena Museum in Texas, a ray of hope after a tough year of remote school and family unrest.

And in Sacramento, Stacy Estes would have bought a car so he could go to work by himself without having to schedule shifts around his fiancée’s workday. Any car would work as long as it fits into their budget.

But these fathers, all of whom owe thousands – in some cases tens of thousands – of old maintenance debts, did not receive the first federal economic checks. Instead, California ripped away what would be a food and shelter lifeline during its worst public health crisis in a century, and checks to pay off decades of debt.

The same thing happened when Estes registered as unemployed. His weekly checks went from about $ 80 to just over $ 60, not nearly enough to cover groceries, rent, and utilities.

Across the state, many of California’s low-income parents have been intercepted with federally collected alimony payments for their $ 1,200 check issued in Spring 2020 along with improved unemployment benefits last year. California responded in good faith to stop the seizures in the second and third round of stimulus checks. David Kilgore, director of the Department of Child Support Services, said the state has given families priority by giving economic funds to custodial parents.

Still, the records verified by CalMatters and The Salinas Californian showed the state held a record $ 430 million last year, up 16% year over year, with essentially taking from one government pot to repay another .

Billy McCasland photographed on April 29, 2021 at his parents’ home in Modesto. Photo by Anne Wernikoff, CalMatters

Parents with child maintenance debts told CalMatters they never saw their stimulus checks and federally funded $ 600 unemployment checks – and the money didn’t always go to their children, either.

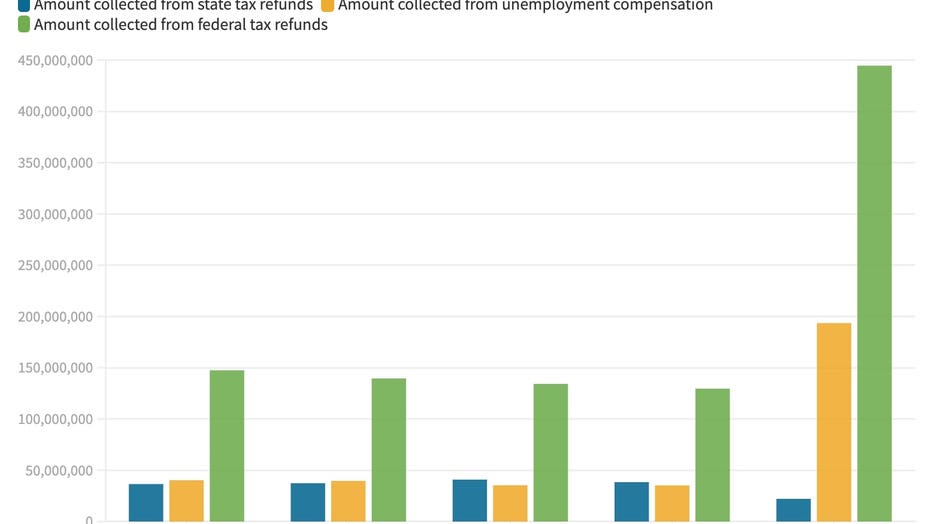

History of Child Support Collections

Based on the idea that people who receive public assistance have an obligation to repay the government, California intercepts child support for children of custodial parents who sign up for state grants like CalWORKS. It imposes penalties such as interest and driving license revocation if the parents who do not have custody are in default.

As a result, California is demanding millions of dollars in overdue maintenance payments from parents without custody, making it nearly impossible for many to find employment, support their children, and pay off debts.

California typically raises approximately $ 2.5 billion each year from parents through the Department of Child Support Services. Most of the money goes to the guardians, but the state agency withholds some of it. In 2019, it retained approximately $ 370 million, half of which went to the state’s general fund.

Those numbers – from collections to withholdings – have skyrocketed in 2020, according to state data, due to Congress-approved state fundraising, which left people on the verge of an eviction cliff during the pandemic. Last year, the agency kept about $ 430 million of the $ 2.8 billion it raised and sent $ 207 million into the treasury, an increase of about 25% year over year.

Stimulus checks and unemployment benefits were such a large portion of the money intercepted that it drops the percentage normally charged through income withholding, where the agency takes money directly from the paychecks of non-custodial parents. The downsizing also contributed to the decline.

Source: California Department of Child Support Services (Table 4.4.1)

Typically, income withholding accounts for 75% of the billions raised, but in 2020 the percentage decreased by more than 20 percentage points.

The interception of stimulus checks fell into the federal tax refund category, which tripled from 2019 to 2020.

Catching unemployment benefits jumped even higher after Congress approved the $ 600 base payments approved under the CARES bill. In 2019, the state agency seized $ 33 million in unemployment benefits. In 2020, that number rose to $ 193 million. The state did not deal with intercepting unemployment benefits.

That means stimulus checks and unemployment benefits from Estes and others were primarily responsible for the surge in child benefit collections during the pandemic.

Pay the parents first

While the most recent checks of $ 1,400 and $ 600 cannot be intercepted by the state on behalf of parents, in many cases the first check was intercepted to pay off old debts to the state and the federal government, Kilgore of the Department of said Child Support Services.

The interception is typical of federal funds like tax returns. It’s an easy way to get extra cash to pay off a parent’s debt to the agency.

Knowing the funds would be intercepted and the food and housing insecurity that sparked the pandemic, Kilgore said, the agency worked with Governor Gavin Newsom to create an executive order that would send the intercepted stimulus checks to custodians first Parent and not to the government.

Newsom issued an executive order in April 2020 that would allow “federal economic controls to flow directly to custodians who have repaid child support.”

However, if the family was not due, the rest went to the government to repay old debts.

Golden State stimulus checks cannot be intercepted. However, according to the Franchise Tax Board, they can still be collected via a bank levy for late child support payments.

As a result, the amount of child benefit funds California kept for itself increased from $ 166 million to $ 207 million between 2019 and 2020.

Lost opportunities

Stacy Estes urges DoorDash to keep up with the state’s debt for child support. Photo by Anne Wernikoff, CalMatters

Stacy Estes urges DoorDash to keep up with the state’s debt for child support. Photo by Anne Wernikoff, CalMatters

Lawyers were outraged by the state’s decision to keep money for themselves during the pandemic. The rerouting of economic checks meant less money for families to pay rent or utilities, said Mike Herald, director of policy advocacy for the Western Law Center.

“There are millions of people in California who lost their jobs at the start of the COVID crisis, and that means those dollars were used instead to pay child support arrears,” he said.

Several fathers who owe tens of thousands of old maintenance debts shared letters they received from the state in lieu of their $ 1,200 stimulus checks. The letters said the checks were intercepted on behalf of the Department of Child Support Services.

For them, that lost money meant lost opportunities.

This article is part of the California Divide, a collaboration of newsrooms studying income inequality and economic survival in California.

Comments are closed.